Tension drives fiction, and successful writers are adept at the dance of teasing out tension, building it to nearly unbearable levels, and then releasing it satisfactorily.

Tension may be high, with life-or-death stakes, or mild (think a cozier read). Different audiences even have varying levels of tension they can take. A friend of mine gave up on Ozark because it was “too tense.” (And yes, somehow we’re still friends.)

What Is Tension in a Story?

Tension is the threat of something happening, good or bad, leading to suspense. Many different kinds of tension can be identified across all genres: sexual, the threat-of-danger, and tension from wanting to achieve a goal, to name a few.

Tension generated by fiction has a profound effect on readers. It causes mental and physical strain, and it has demonstrable physiological effects.

By building tension, authors intentionally stress their readers. But not all stress is bad, and writers (at their best) deliver the kind of stress that challenges, exhilarates, and even promotes growth.

Tension Literary Definition

Tension in literature keeps readers engaged because they are interested in what will happen next.

Tension refers to the suspense, anticipation, and uncertainty created by conflict.

Types of Tension

There are two types of tension: internal and external.

External Tension

External tension arises from the main conflict for your protagonist. This relates to that character’s goals, the character’s motivation, and the opposition to those goals.

In quest tales, a character must go on a journey to win the object of the quest. If the stakes are high (that is, if failure to win the object results in catastrophe for the character or their world) and the opposition is a compelling, genuine threat, then there will be tension as to whether the character will succeed.

Internal Tension

Internal tension usually arises from a character flaw that the protagonist must address (the inner goal rather than the external goal). The movement of the character toward this inner development also relates to goals, motivation, and opposition.

Inner tension can be just as weighty as its external counterpart, if not more so. With these two types of tension at play, more tense moments can result from the friction between achieving external and internal goals that are at odds with each other.

A character might succeed at their external goal and fail at their internal one, or vice versa. Indeed, this is often the case in some of our most successful, impactful stories.

Tension and Pacing

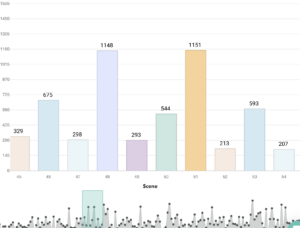

The length of scenes has an effect on tension and pacing. Whereas a succession of short scenes may propel the reader forward as the protagonist races to a goal, longer scenes can be employed to play out the conflict as the culmination of this activity.

Longer scenes are also often necessitated for your major plot points: the inciting incident, plot point 1, midpoint, plot point 2, and climax and resolution.

Longer scenes are also effective for letting tense moments build through the slow accumulation of detail needed to drive the more frantic pace that will follow.

Word count per scene is easily viewed as a visual insight in Fictionary, and you can find more information in this “Evaluate Pacing of Your Novel Using Word Count per Scene” article, here: https://fictionary.co/journal/evaluate-pacing-of-your-novel-using-word-count-per-scene/

Five Tips for Building Tension

The following are five tips for building tension, but keep in mind that the foundation always lies in well-developed, active (not passive) characters.

Creating characters readers care about and want to follow (into the wardrobe, into a new relationship, into outer space, through hell and back) is always the first step toward creating tense scenes and stories.

Tip 1: Make the Most of Your Setting

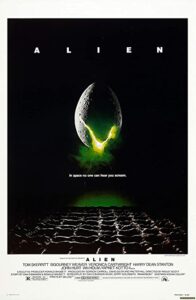

“In space no one can hear you scream.” Characters are always trying to flee the haunted house, but the brilliance of Alien is that death awaits as surely without (in cold, dead space) as from within (the creature). The tight confines of the ship serve to further the tension.

Setting can take characters out of their comfort zone, whether placing them in peril (pursued across the desert by a maniac) or setting them up for a different kind of tension entirely (thrusting seemingly reluctant lovers into a one-bed scenario).

Tip 2: Employ a Ticking Clock

Usually associated with thrillers, the ticking clock puts characters under pressure, forcing them to act to avoid the consequences of that metaphorical clock striking midnight.

The clock, in whatever form it takes, presents writers with the delicious opportunity to see how their characters act under this pressure. Will they do something they regret? Will they make choices with unpredictable outcomes? Yes and gloriously yes.

Tip 3: Take a Rest

Horror at its best knows just how to play with its audience, when to slowly build dread and when to release it with a jump scare or a laugh. Good horror writers know that the ebb and flow of tension keeps their readers off balance, and it is the quiet moments that allow the reader to recharge, preparing them in this way for an even higher level of tension to come.

Tip 4: Play with Reader Knowledge

Imagine a Western where the protagonist enters a bar, not knowing that the character he encounters there has come for the express purpose of killing him. If the reader has this knowledge that the protagonist doesn’t, the ensuing interaction will be super tense.

Tip 5: Concentrate on Obstacles/Stakes

As mentioned earlier, big stakes mean tense scenes. This, however, doesn’t necessarily entail world-ending schemes from master villains. A snub from a high school crush can seem like the end of the world, so it’s up to the author to sell the importance of the stakes to that character.

The placement and degree of stakes in your story is also important. If a character has to vanquish a succession of monsters, defeating the scariest monster first will decrease tension in the subsequent encounters. Readers need to be kept off balance, and surprising them with ever-increasing challenges is a way to do it.

Tension Examples in Literature

Almost every fiction book contains tension, but some have more than other. Here are ten excellent examples of tension in literature:

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley: The clash between individuality and conformity in this dystopian society governed by genetic engineering and mind control fuels the narrative’s existential and philosophical debates.

- 1984 by George Orwell: Winston’s struggle against the oppressive regime of Big Brother intensifies as he grapples with his desire for freedom against his fear of being caught.

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen: The social tension between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy gradually transforms into romantic attraction despite their initial dislike and misunderstandings.

- Matilda by Roald Dahl: Matilda’s intelligence and telekinetic powers empower her to stand up against her bad parents and the tyrannical headmistress.

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins: Katniss Everdeen’s survival in the deadly arena where only one may survive is juxtaposed with her inner turmoil over her feelings for Peeta Mellark and her responsibility to her family.

- The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood: Offred’s internal conflict between survival and rebellion intensifies as she navigates the oppressive regime of Gilead. She is stuck between protecting herself and trying to protect her daughter.

- The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern: The magical competition between Celia and Marco intertwines their destinies, leaving readers on the edge of their seat until the very last page.

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll: Alice’s journey through Wonderland challenges her perception of reality as she encounters eccentric characters, absurd situations, and the tyrannical Queen of Hearts.

- Ready Player One by Ernest Cline: Wade Watts’ quest for the Easter egg hidden within the VR world of the OASIS pits him against real-life rival gamers and a powerful corporation, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy.

- The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid: Evelyn Hugo’s glamorous yet tumultuous life, revealed through a series of interviews with a young journalist, uncovers the secrets, scandals, and sacrifices behind her legendary career and marriages.

Final Thoughts on How to Write Tension

Play with tension. See how high you can ratchet it (and don’t worry about my friend; I promise he’ll be just fine).

Build your tension-crafting skills and learn to raise and lower it as though you’re turning a dial. You’ll have fun with it, and your readers will come to count on you for delivering a tasty concoction of tense scenes that will keep them reading late into the night.