Learning the craft of writing is not only learning how writing concepts work, but also learning how you work—as a writer. You cannot just read a how to create a plot for a story blog without first looking at the fundamentals of writing.

First, what type of writer are you? What are your story needs? And how do you create a plot for a story and where do you go after that?

Whatever that stage of writing you are at, whatever type of writer you are, there is joy to be had in creating a plot for a story—the Fictionary way.

A plot made by a garden designer or a garden nurturer

The writing world likes to draw lines in the soil. Where some folk stand on their allotted side telling the world that their method is the ONE that works. Whilst others stand on the other side and argue till they are green in the face that theirs is the ONLY method that works.

Try different methods, find your own way, one that opens up your writing world.

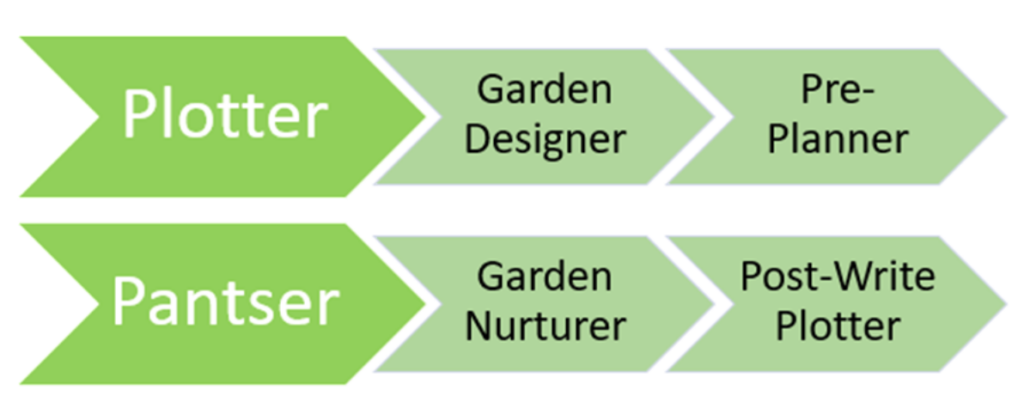

Let’s look at the two main writer types. They have many names, but the respective concepts are pretty much the same whatever the name. It’s all a question of timings.

A Plotter plots first, then writes.

A Pantser writes first, then plots.

Are you a Plotter, a Garden Designer, a Pre-Planner? Are you like a garden designer, you have plans, drawings and insight to where you will sow every story seed? You know where the story is going to start and there will be exactly 84 scenes and you know where the protagonist is going to end up. Great. You are in fabulous company; many successful writers use this method: such as JK Rowling, John Grisham, amongst many more, as this Goodreads article shows.

Or are you a Pantser—someone who writes by the seat of their pants, a Garden Nurturer, a Post-Write Plotter? Are you like the gardener who plants the seeds of your story arbitrarily, and nurtures those seeds, then those plantlets as you write? Only getting the bigger picture at the end. Armed with a pair of literary secateurs, you cut back your story in the post writing stage. Great. You too are in fabulous company; many successful writers use this method: such as Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, amongst many more.

Whichever writer you are, a story needs a plot. And the plot needs to be created at some point.

Really, all writers are on the gardening writer’s spectrum, either being the Garden Designer writer, or Garden Nurturer writer or somewhere in between. This is great as in the garden are where the story flowers grow.

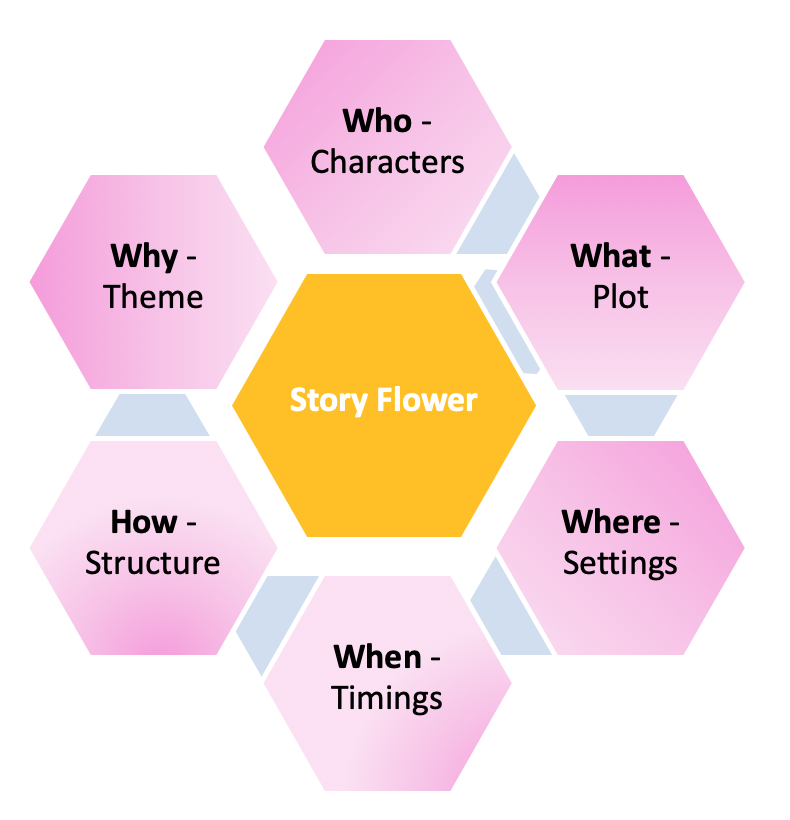

The Story Flowers what?

Inspired by Roy Peter Clark’s reports vs story questions from his phenomenal book—Writing Tools, I have tweaked those questions a tad, and put each question into a Story Flower petal.

Think of a story as a flower. Each petal of the Story Flower answers a pivotal story question. All the petals need to be answered to make the Story Flower strong, full of life, memorable. If you have one or two raggedy petals, then your Story Flower is unsellable, and is discarded on your story florist’s shop floor.

In this blog, we’ll be focusing on the plot petal, so you can learn how to create a plot for your story.

What is a plot?

Kristina Stanley has a great discussion about Plot vs Story. Remember that the plot is ‘what happens’ in a story.

From a plot idea to a plot with wings

Before you create a plot of a story, you will start with an idea for a plot. A plot idea is most like a caterpillar. A hungry caterpillar that eats through every bit of research you put before it. But then the day comes to write, in the safety of a writerly cocoon.

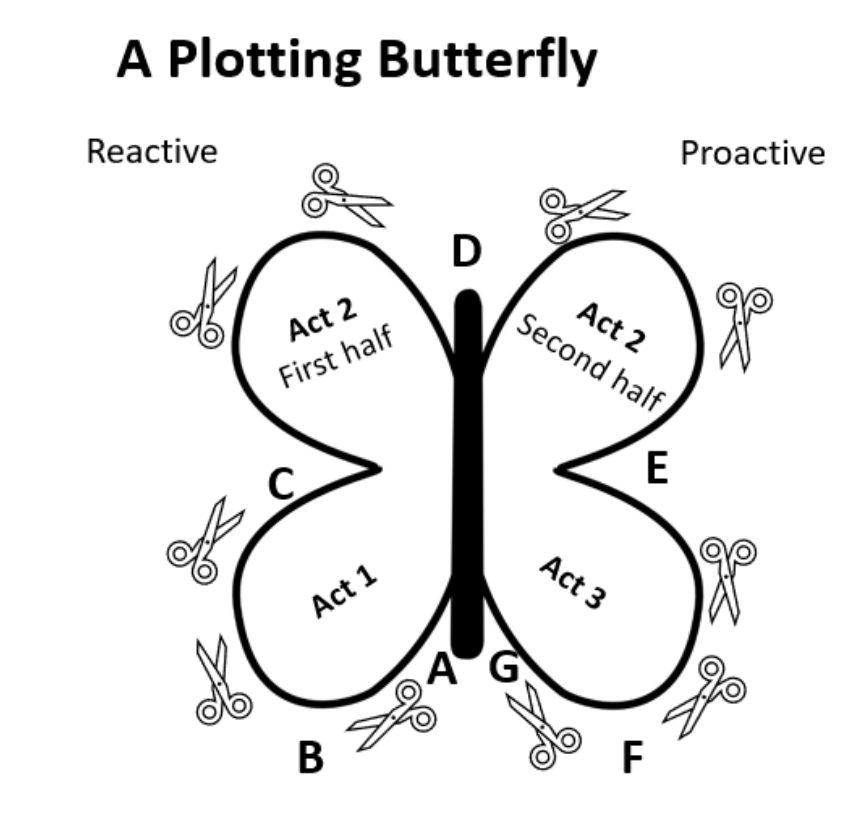

In the real world, only caterpillars know how butterflies are created inside those cocoons. In the story world, I will show you how to create a plot for a story using a plotting butterfly, a Plotterfly. This insight holds true if you plot before or after your first draft.

Stories have symmetry

Stories have symmetry. Symmetry can be seen between the Protagonist versus the Antagonist; symmetry between the first half conflict and the second half conflict of the plot; symmetry from the initial world order to the final world order.

Understanding the plot symmetry is easiest when you look at the shape of a butterfly. The symmetry of a butterfly is both simple and complex. Just like a plot.

Let’s get introduced to:

The Plotting Butterfly—the Plotterfly

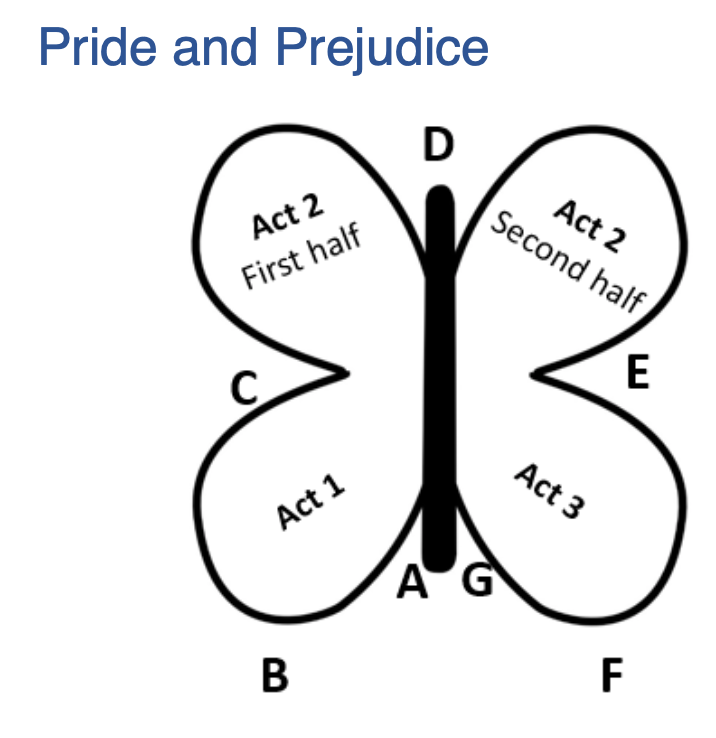

Back in kindergarten, do you remember your teacher asking you to cut out a butterfly? You would have started at the point A, and been told to cut around to point B, then point C, through each of the points to point G?

Back in kindergarten, do you remember your teacher asking you to cut out a butterfly? You would have started at the point A, and been told to cut around to point B, then point C, through each of the points to point G?

These cutting points and their placement are super important as they correspond with the major Plot Points found in your plot.

Those 7 major Plot Points are:

A. Initial Scene – everyday life for the protagonist

B. Inciting Incident – an irreversible moment

C. Plot Point 1 – steps into a different “world” full of potential

D. Middle – hints at the Final Scene

E. Plot Point 2 – the lowest moment, potential seems dashed

F. Climax – has everything learnt so far been enough

G. Final Scene – mirrors the initial scene, more powerful version of Middle

In stories, the initial scene reflects the final scene, the Plot Point One is when the protagonist enters a new world with new potentials. Plot Point Two, the protagonist’s world seems to crumble, all potential dashed. This mirroring, the intensity of each plot point and their intervening scenes has to equal the plot points further along the plot.

The Plotterfly’s curves of her wings, area inside her wings, reflected patterns against her corresponding wing, show where the symmetry for your plot should be.

Look back at the Plotterfly diagram

Now look at those letters on the Plotterfly. The first half of the Plotterfly is the first half of the plot, the second half, that’s the second half of the plot. All pivoting at the body, on the middle scene. At this middle point, the story goes from a reactive to proactive protagonist.

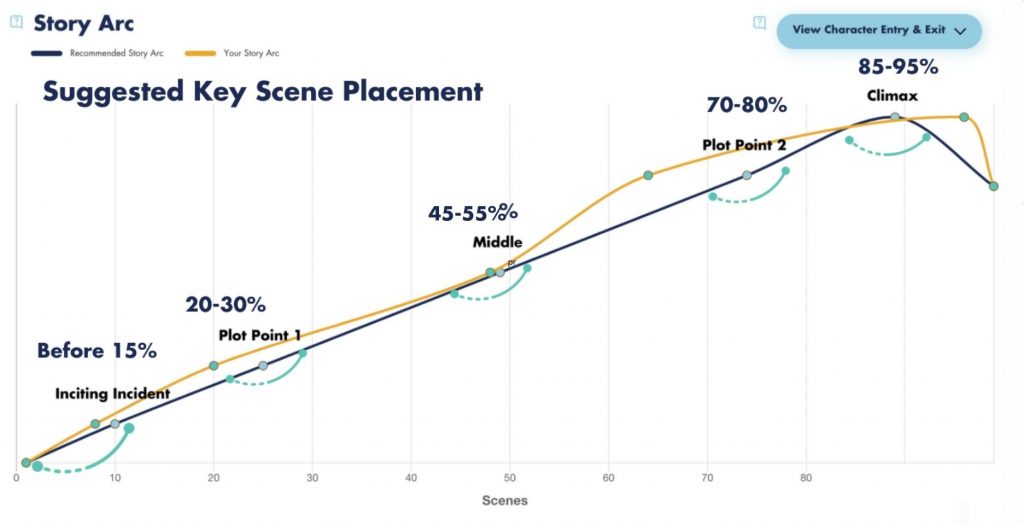

When you put your first draft into Fictionary, it will draw your plot line on a graph much like this one:

To understand the proportions of the Fictionary graph, look at the proportions on the Plotterfly. This will help you with the plot of your story.

Each Plotterfly wing houses 25% of the story. Between Plot Point 1 and Plot Point 2—points C, D, E on the Plotterfly—lies 50% of the plot. The two upper wings are the two halves of Act Two.

If you ever get into bother with Act Two, remember whatever conflict you set up in the first half of Act Two, your protagonist faces it in the second half. Just follow the butterfly’s wing patterns, and you will not lose any sense of your story’s proportions.

Pride and Prejudice

Here is Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice on the Plotterfly:

A. Initial Scene – A couple arguing.

B. Inciting Incident – Darcy rejects Elizabeth at the ball

C. Plot Point 1 – Elizabeth in familial disgrace, she rejects Mr Collin’s proposal, Elizabeth accepts her spinsterhood ahead.

D. Middle – Elizabeth rejects Darcy’s proposal, uneasy with one another.

E. Plot Point 2 – Whole Bennet family in social disgrace, no possibility of future proposals, Elizabeth distraught by her spinsterhood ahead.

F. Climax – Elizabeth accepts Darcy’s proposal.

G. Final Scene – A couple at ease with one another.

Keep thinking about that Plotterfly: the reactive side, the proactive side, the pivot scene. You have your plot.

More on the plot of a story

Now you know how to create a plot for a story, using the Plotterfly, you might want to read Sherry Leclerc’s fabulous blog about plots, which talks about plot beats, and gives some great examples.

Got plot, now what?

Fictionary helps you focus on all your story elements. You can take your first draft and check each scene, ensuring each Story petal element is robust, strong, polished.

Your story will blossom with Fictionary.

Post Written by L Cooke

As a Fictionary certified Editor, I will explore your Work-In-Progress, chapter-by-chapter, scene-by-scene, story-element-by-story-element. You will end up with a treasure map of sorts, full of actionable advice and a greater understanding of your Work-In-Progress.

As a Fictionary certified Editor, I will explore your Work-In-Progress, chapter-by-chapter, scene-by-scene, story-element-by-story-element. You will end up with a treasure map of sorts, full of actionable advice and a greater understanding of your Work-In-Progress.

Contact at: https://invermuse.co.uk/