Before we cover “How to Edit a Cozy Mystery”, I’d like to introduce Ryan Rivers. Ryan is enrolled in the 2021 October Fictionary Certified StoryCoach program and is a developmental editor, specializing in mystery fiction and crime fiction.

So over to Ryan…

Killer Tips for Editing a Cozy Mystery

The cozy is one of the heartiest sub-genres in the robust mystery genre. Agatha Christie remains the cozy queen, and her novels, shorts, and plays established many of the tropes that modern readers still expect and demand.

I’ve devoured cozies for over 30 years—everything from the novels by Christie to the movie Clue to the TV show Psych. I love spending time with these amateur detectives as they puzzle out a mystery and restore justice to their community. To me, the “c” in cozies stands for community, and the theme of community is why I also edit and write cozies.

You might edit cozies too, or perhaps you’ve had an increase in authors who need a story edit. If so, here are some tips to better understand the genre and help your author-clients craft their best book.

Tip #1: Know the Genre

Editing genre fiction requires an awareness of the specific rules and conventions. By rules, I mean required story elements that make a cozy a cozy. By conventions, I mean ways authors vary the rules to make their cozies seem fresh to readers.

Readers attracted to cozies often have a strong sense of justice. When a crime is committed, they join the protagonist in the investigation, collect and analyze the clues, and confront the villain at the climax. It’s this final closure—bringing the villain to justice and restoring harmony to the community—that readers crave, as their own world is often unpredictable, ambiguous, and chaotic.

And it’s this idea of community that establishes the first rule of cozies: a contained or isolated setting. Popular examples include small towns, cruise ships, or English country homes. In early chapters, the setting is described as quaint and idyllic… until some horrendous crime occurs. The setting descriptions then reflect the tension and anxiety related to the crime.

A Cosy Mystery Including Halloween Hoedowns Can Be Deadly by Ryan Rivers

The cozy protagonist is always an amateur sleuth with a profession that gives her access to information or a rotating group of suspects (especially useful for series). Popular professions include newspaper reporter, teacher, café/bakery owner, and librarian. Cozy protagonists are often female and typically younger millennials (like Aurora Teagarden) or octogenarians (like Jessica Fletcher). These protagonists often draw on their professional expertise to solve the crime.

Cozies focus on the characters’ emotional response to the crime (usually murder), and an absence of blood, violence, sex, and profanity. No children or dogs are harmed in cozies, and I wouldn’t even risk putting either in jeopardy.

Authors can create a variety of original stories by adhering to these rules but modifying the conventions. For example, the protagonist in my Bucket List Mysteries is male and Japanese American. In my case, Sho Tanaka still adheres to the rules of the cozy protagonist—he’s a nurse with an emotional wound who escapes to a small town in Texas and unexpectedly applies his expertise to solve crimes. Modern cozy authors often deviate from the traditional norms to create diverse and culturally rich stories.

How to Edit a Mystery: Tips

If you’re new to editing cozies, read the book descriptions of the latest bestsellers. Those should reveal the story’s premise and conventions, like the setting and protagonist. Every online retailer categorizes cozies differently, so experiment until you find the system that works best for you.

I also recommend asking the author for a list of comps—the published titles that are comparable to the author’s manuscript in some significant way. It’s possible the author has no comps, and that’s okay. As you edit and read more in the genre, you’ll develop a working list of your own. However, when authors hire you for a story edit, they are signaling they want an elevated level of help with their story. Relaying how a comps list can help them hone their craft and market their finished manuscript is one tangible way to show the value of editing.

Tip #2: Rough Up the Protagonist

If you read the 3-star and lower reviews of bestselling cozies, you’ll notice a trend related to the unpleasantness of the protagonists. But creating “likable” protagonists can be challenging.

Since the sleuth is an amateur, she won’t have the authority of law enforcement or the access to the crime scene or murder suspects. This means she’ll have to get resourceful. Turn on any episode of Murder, She Wrote, and I bet Jessica Fletcher is somewhere she’s not supposed to be or being escorted out of somewhere she’s not supposed to be. There’s a thin line between endearingly curious and annoyingly snoopy.

As a cozy reader and editor, I often interpret readers’ comment about the likability of the protagonist to mean the protagonist isn’t relatable. This is an area where story editors can help.

Authors often miss opportunities to humanize their protagonist in ways already built into the cozy rules. Act 1 builds toward the inciting incident, or the discovery of a crime. However, there’s another incident that rocks the protagonist’s world; it’s the reason she left her old world for the new one. Common examples include the protagonist inheriting a house or a business from a deceased family member, leaving a high-powered “city” career to care for a beloved family member, or starting over after a divorce/breakup.

But authors often gloss over what brought the protagonist to her new world, treating it as a plot device instead of a way to develop the character and foreshadow how she’ll investigate crime. In fact, these backstories are often delivered as exposition in the early chapters, depriving readers of an opportunity to relate. If readers can’t connect—and connect early—with the protagonist, they’ll grow increasingly annoyed with her meddlesome behavior.

How to Edit a Mystery: Tips

Help authors make their protagonist more relatable by developing their backstory/emotional wound. For example, if the protagonist moved to her new world after a divorce, help the author expand how that event informs her decision to solve the crime, how she interacts with law enforcement and suspects, the techniques she uses to investigate, and the filter she applies when evaluating clues or motives. These behaviors reflect the protagonist’s biases and are typically why she fails early in the investigation. Ideally, solving the crime—and restoring justice—helps the protagonist heal, but her past will continue to challenge her in the next book (if part of a series).

Don’t be afraid to rough up the protagonist. Readers may not want explicit violence and sex, but that doesn’t mean they want a sterile plot and bland characters.

Tip #3: Create a Worthy Villain

In Act 3, the villain must be unmasked, justice served, and harmony restored. An author’s success rate here depends on their villain.

In cozies, the villain is not a contract killer, serial killer, random psycho, or literal monster. They could be the PTA president, a next-door neighbor, or a family member. Cozy villains are often citizens of the community who one day reach their breaking point and commit a crime.

I often find the villains are the least developed characters in cozies. Authors are so worried about “hiding” the villain from readers that they create bland or rarely seen individuals. If this happens, readers will be surprised—just not how the author wants. Readers will not only lose interest in those final chapters, they’ll feel cheated by the author. The story has not fulfilled its expected premise, and, if writing a series, this will impact an author’s read-through rate.

How Many Villains?

Most cozies include 3–7 viable suspects (the number often relates to manuscript length). They all have a motive, but only one committed the crime. When did the villain decide to commit the crime? What event triggered them to this point of no return? These are often neglected questions, but the answers are opportunities to develop character. The villain’s motive must be personal. This is a community member who makes the calculated choice to disrupt that community. Why? The answers to these questions add dimensions to villains, and they might even make them somewhat relatable to readers. If you can make readers squirm a little because they can rationalize why the villain believed the victim had to die, you’ve done your job as a writer.

How to Edit a Mystery: Tips

I’ve known editors who ask the author upfront whodunit. I don’t recommend this strategy. Part of the thrill of reading cozies is investigating alongside the sleuth and discovering whodunit together. Editors have one chance to experience the story like a reader—during the first pass. The first pass will help you evaluate the surprise element of the villain’s identity and also get a sense of their motive and their trigger (or the event that led to commit the crime).

For helping authors create stronger cozy villains, you might find it helpful to edit backwards, beginning with the climax where the motive and trigger are revealed. Once you understand both, you can help the author foreshadow them in the earlier scenes; most villains get an introduction scene and 1–2 interview scenes. Threading these elements throughout the manuscript makes the eventual unmasking logical to readers. Authors may express some concern that these editing techniques make their villain more obvious to readers, but this same character work should also apply to the other suspects.

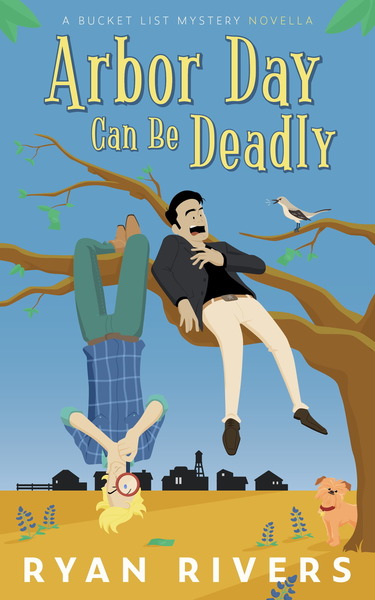

If you’re interested in how I apply these rules and conventions to my own cozies, download my free novella. Arbor Day Can Be Deadly is part of the Bucket List Mysteries series. This 40,000-word novella introduces ICU nurse Sho Tanaka, former TV tween detective Levi Blue, and the community of Bluebonnet Hills, Texas. Visit my website at www.ryanriversbooks.com and click on the link “Get Your Free Mystery!” You’ll be added to my newsletter, but you can unsubscribe at any time.

If you’re interested in how I apply these rules and conventions to my own cozies, download my free novella. Arbor Day Can Be Deadly is part of the Bucket List Mysteries series. This 40,000-word novella introduces ICU nurse Sho Tanaka, former TV tween detective Levi Blue, and the community of Bluebonnet Hills, Texas. Visit my website at www.ryanriversbooks.com and click on the link “Get Your Free Mystery!” You’ll be added to my newsletter, but you can unsubscribe at any time.

And if you enjoy the novella and want more of Sho and Levi, consider reading my short story “Halloween Hoedowns Can Be Deadly,” which is part of Once Upon a Halloween: A Wicked and Wild Cozy Anthology. You can find this story only on Amazon.

Ryan Rivers

Ryan Rivers is a developmental editor, specializing in mystery and crime fiction. He’s also the author of the Bucket List Mysteries, a comedic cozy series featuring ICU nurse Sho Tanaka and former tween TV detective Levi Blue.

Ryan Rivers is a developmental editor, specializing in mystery and crime fiction. He’s also the author of the Bucket List Mysteries, a comedic cozy series featuring ICU nurse Sho Tanaka and former tween TV detective Levi Blue.

Professionally, Ryan has worked in higher education and academic publishing for over two decades. He’s a former deputy editor-in-chief of a professional communication journal and a book editor for a series on professional communication for engineers and scientists.

By day, he teaches technical writing and stops the spread of unnecessary adverbs and vague pronoun references. By mid-afternoon/early evening, he solves crime with his trusty sidekick/toddler son. Together they have uncovered who, in fact, has got your nose and tracked the elusive Peekaboo. They live and eat and occasionally sleep in North Texas with their Brussels griffon pup.

For more information, visit Ryan at www.ryanriversbooks.com/editing or email at [email protected]

![]()

A Fictionary Certified Story Coach helps writers tell better stories and makes a writer’s voice shine! If you’re not ready to become a certified coach but need a tool to help you become an exceptional editor, try Fictionary StoryCoach for editors for free!

Learn more about becoming a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach.

Ready to become a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach? Check out Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Training and become a cutting-edge structural editor for fiction.

Special Discount

If you’d like to take the training, send me (Kristina) an email at [email protected] telling me why you’d like to become a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach, and I’ll give you a discount.

The next program starts on February 1st, 2022, and spaces are limited.